In this project, there are conversations among faculty, students, and staff that include cultural references that are problematic, reflected in terminology, attitudes, and biases. Neither Muhlenberg College nor the Muhlenberg Memories Project condones these references, but include them in the interests of historical accuracy.

In the summer of 1968, Muhlenberg launched the Educational Opportunity Pilot program (EOP). Approved by the Academic Policy Committee, with the support and leadership of Dean Philip Secor, the EOP was meant to increase diversity on campus by offering scholarships to economically disadvantaged Black students from Harlem, Philadelphia, and other urban centers.

In one of the few historical accounts of Muhlenberg’s Black alumni in the EOP, student writer and activist Diane Williams ‘72 left a legacy to be explored. The research of Giovanni F. Merrifield ‘23, conducted in Summer 2022, revisits Williams’s legacy to gain a deeper understanding of the College’s history of diversity and of the EOP. Williams left behind written accounts of the EOP experience through her Muhlenberg Weekly articles, essays, and poems. Without a doubt, the EOP was premised on good intentions. But the best of these good intentions didn’t address the EOP students’ need to feel they belonged. Instead they faced an unwelcoming culture of whiteness.

Adding more depth to this biographical work, Merrifield captured oral histories of Diane’s friends and family, recovering narratives to illustrate that historic moment in which Diane was an activist, leader, and teacher at heart. Interviewees included Kenya Albert, Sally Barbour ’71, Janice Bergstresser ’73, and Marc Parilli ’69. Special thanks also to Sallie Keller Smith ’73.

Diane Williams used her voice as a platform to speak up and shift the climate at Muhlenberg. Her words were used as powerful weapons to fight the battle of injustice and racism.

“She had a fierceness about her that she knew what was right and wrong type thing…She had a really strong background of right and wrong and fairness and equality”

~Sally Barbour ’71

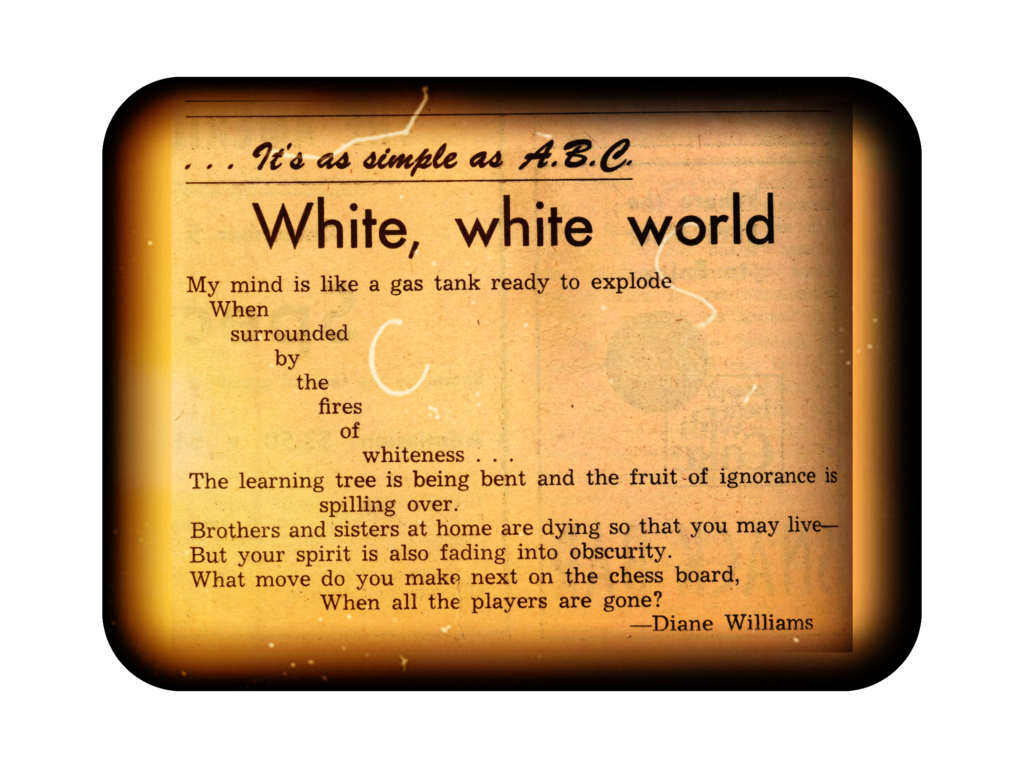

[white white world]

She was an activist just by being on campus, a voice for the Black community, to tell her truth and her EOP classmates’ truth about the exhausting and often othering experiences on campus. The origins of her powerful influence and struggle can be traced to her roots in Harlem.

Diane’s mother and aunts nurtured her growth and development at home in a Harlem brownstone. While there was little money and while her life was a struggle, she realized the imperative for Black voices to speak up, to speak out against television’s depictions of the Civil Rights Movement.

As Williams would write in a 2013 blog post,

“I grew up during the Civil Rights Era. So many of my memories are studded with the fight for equality and justice. As a child I ate dinner while I watched African American youth hosed by firefighters, beaten by cops, and bitten by dogs simply because they wanted the right to vote and have a decent education.”

Outside her home, influences came from the streets, sidewalks and community venues, where civil rights activist leaders such as Malcolm X, Queen Mother Moore, Preston Wilcox, and the Black Panther Party spoke about how the Black community could obtain equality and equity, both socially and economically. With these influences and with her private high school education onboard, she left a sense of place and belonging that Harlem offered to pursue a college education.

In March 1968, Dean Secor’s announcement about the Educational Opportunity Pilot program described the initiative as one of “mutual enrichment,” which will “provide for Muhlenberg’s regular students the opportunity to share with and learn from students whose backgrounds and experiences in the inner-city environment are markedly different from their own.”

The EOP admitted students from Philadelphia, New York and other urban areas and granted them full scholarships as an experiment for “Muhlenberg students to live, work and study with people from the urban ghetto,” but the program made the Black students feel like outsiders.

“All the students were from the ghetto areas of their respective cities. For them leaving for college involved much more than simply leaving behind family and friends. They were to become, in almost every sense of the word, “foreign students.”

~Diane Williams, excerpted from “A Look at the Educational Opportunities Program from the Inside”

The climate was tough for the EOP students. Many were viscerally aware of the battles taking place on campuses and in the streets across the nation. They knew the dangers of being a human while Black. But many were torn between speaking out and finishing college. Despite being a “hotbed of tranquility” as one professor called Muhlenberg, the arrival of Black students on a conservative white campus made Muhlenberg feel like a battleground for acceptance and respect.

“The first semester was to prove itself an often times vexing experience. Everyone was on their guard, watching for the first evidence of prejudice. It came in many forms. Most often it appeared as a strained overindulgence on the part [of] a few students. At times when their [sic] was a reason at all to look for it, there was a great deal of distrust.

As everyone settled down to hit the books, many of the students were plagued with inter-racial conflicts with room-mates. (None of the black students were allowed to room together) At first the only thing for them to do was to make frequent trips home to ‘recharge their batteries.’

To them everything that was soulful was at home. There was no place in Allentown where they could even get a decent plate of “soul food.” The students talked differently and danced differently.”

~Diane Williams, excerpted from “A Look at the Educational Opportunities Program from the Inside”

Diane entered Muhlenberg’s EOP better prepared academically than some other EOP participants. The only Black New York Catholic school, which her mother had struggled to send her to, prepared Diane to be a tutor and a leader for her fellow Black students.

This yearning to teach others, to help fellow Black students succeed, became part of her legacy. Like other Blacks students, she understood how white students would judge a Black student for lacking knowledge around a certain topic, and assume that’s how all Black people were. She knew there would be much generalization of the Black community amongst the white students, so she felt it was her duty to prepare her classmates for what was to come. According to one of her long-time classmates and friends, Sally Barbour, “[S]he was a teacher, a teacher at heart, I would say, and a writer.”

Diane, nonetheless, met her share of prejudice. In one such memorable moment, she confided to her friend, Marc Parrilli ’69, that a psychology professor bluntly told her he didn’t want her in his class. In interviews with Diane’s friends, they shared how the campus wasn’t ready for Black students, that the “professors were totally naive about race relations” (Sally Barbour, 2022).

Diane was involved in many campus activities including freshman orientation leader, Women’s Council, President of Prossser Hall, Who’s Who in American Colleges and Universities, Union Board, Association for Black Collegians (A.B.C.), and a regular contributor to The Muhlenberg Weekly.

In the column, “It’s as simple as ABC,” Diane and a few others in the Association for Black Collegians wrote about their experiences in a white college. In White, White World, she expressed frustration with the cultural ignorance of living in a white world that failed to see the humanity of Black students. The Squeeze was Diane’s effort to frame assimilation as problematic for Black students because they would lose sense of Blackness by the sheer power of assimilation and they felt need to fit in. The Fight Ali Lost shows audiences that even a well-known Black man could be subject to disappointment and anger, especially with his failure to connect to and support the Black students.

Demonstrating not only her passion for offering lessons on cultural awareness, Diane’s drive for activism was evident in her social activities and in student government. For example, in a news article, the Muhlenberg Weekly reported that Diane Williams, acting on behalf of other Black students met with student council to get approved demands for improved financial aid, admission procedures and housing of Black students.

In precient language in a special issue of the the Muhlenberg Weekly, Diane posed the question “From Blackness, Where Do We Go?”

Diane felt it was important to express oneself and have a voice because that is how change happens. Change only occurs when one opens one’s mouth, and that’s what Diane did…and that’s what she encouraged others to do as well.