The Muhlenberg Memories Project

Women’s Empowerment

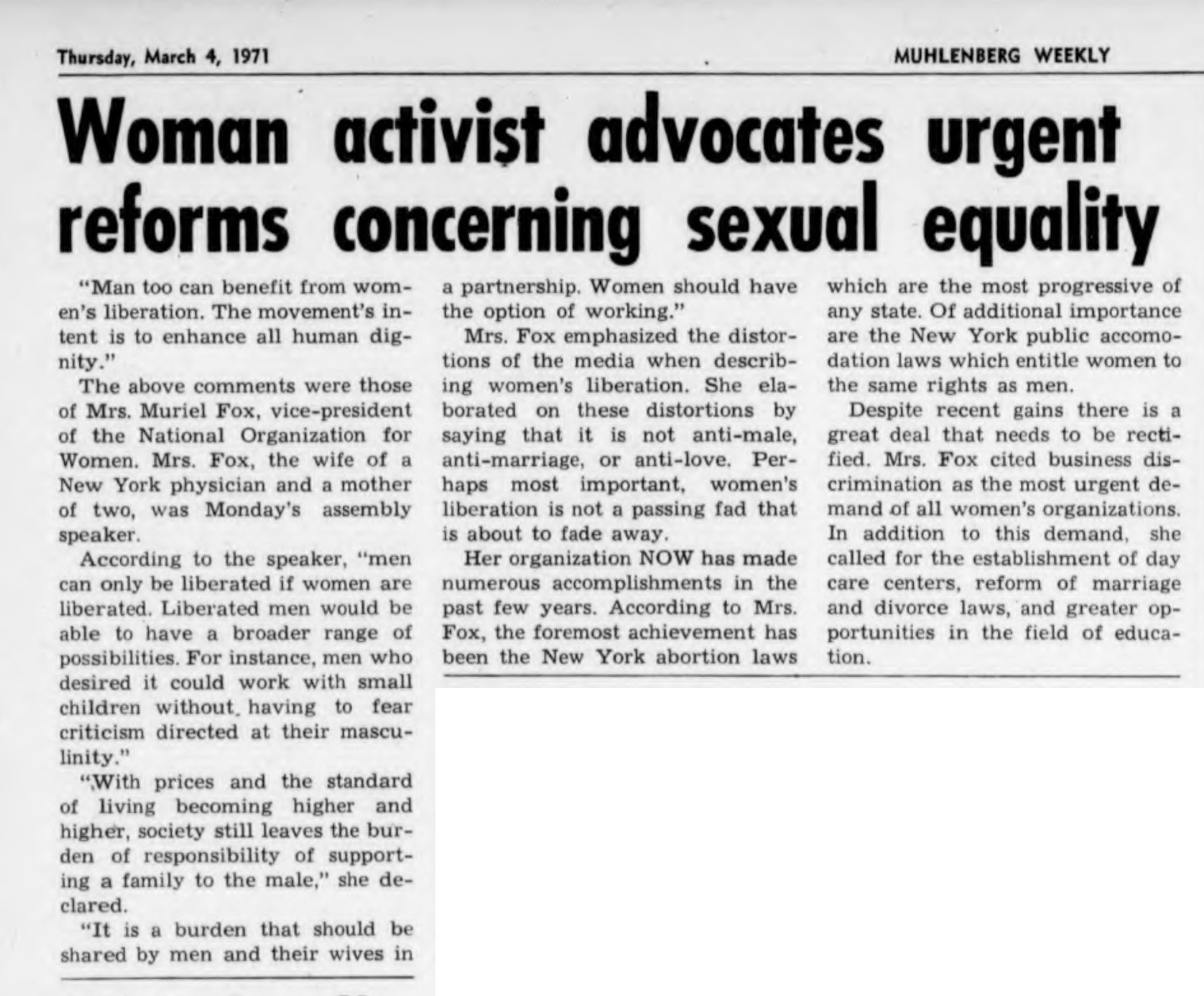

The 1970s saw the strict behavioral codes of the first years of coeducation drop away, much like the term “coeds.” Social norms were changing, and women on campus were pushing back against traditional roles. Ads for abortion clinics began to appear in the Muhlenberg Weekly, alongside photographs of students protesting the Vietnam War draft in downtown Allentown.

According to a study conducted by Dr. Monica Tiscione of the psychology department in 1975 entitled Survey of Attitudes toward Women at Muhlenberg College,

“…the women undergraduate students at Muhlenberg College are, on the average, less traditional and more liberal in their attitudes toward the roles of women in society than are the men….In addition, it is interesting to note that, in general, Muhlenberg women have more liberal, less traditional attitudes towards the roles of women…than do Cedar Crest women.

…The discrepancy between the men’s attitudes and the women’s attitudes may be a source of confusion, irritation, and perhaps even frustration for both groups. It would seem beneficial then to provide as many opportunities as possible for the issue of the changing roles of men and women in society to be discussed openly and constructively within the college community.”

Metzger vs. Muhlenberg College

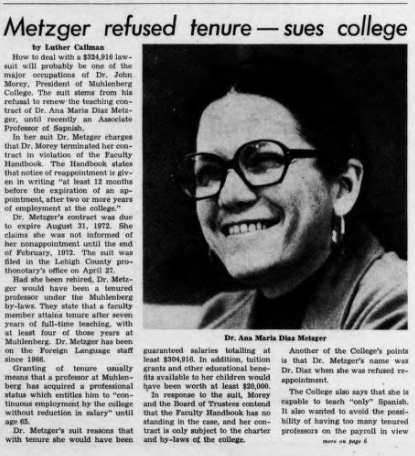

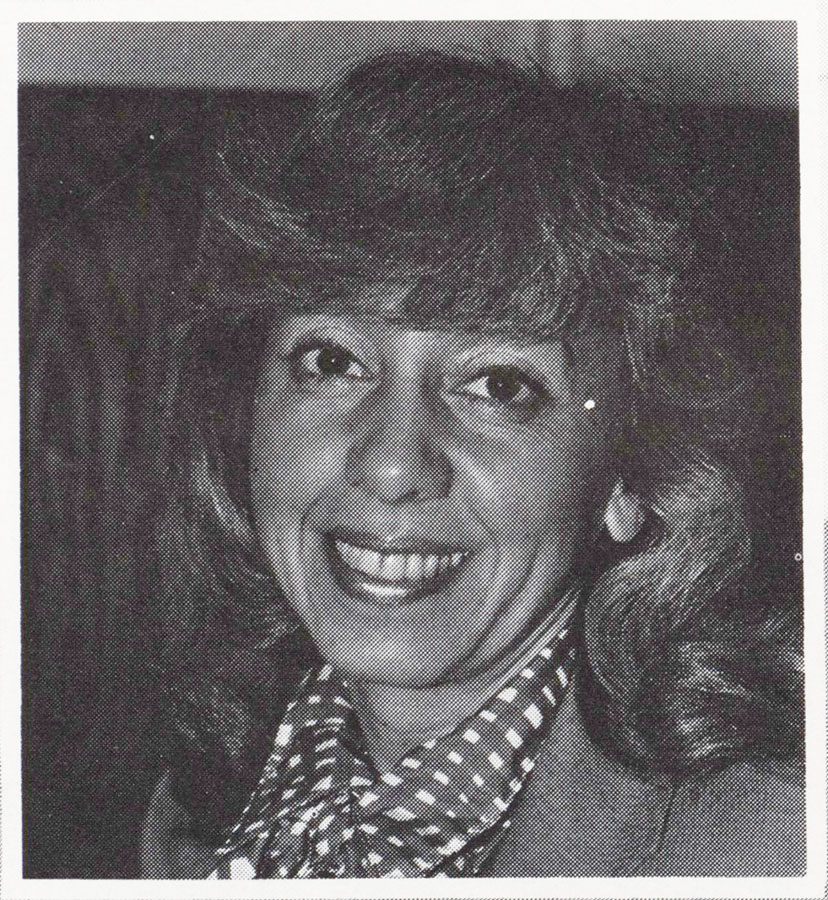

Dr. Ana Marie Metzger joined Muhlenberg’s faculty in 1966 as an assistant professor of Spanish. She was promoted to associate professor in 1970, and she had a record of obtaining research grants, had organized a symposium on Spanish, and had a submitted a book proposal. In early 1972, she was recommended for tenure by her chair, Dr. John Brunner. In February of that year, Dr. Metzger was denied tenure by a vote of 4-2, and she was informed that her contract was to terminate in August, six months short of the customary twelve-month notice.

The College listed its reasons for denying tenure as the following: 1) The faculty personnel committee voted against granting her tenure, 2) The president and dean agreed with the committee, 3) Dr. Metzger could teach only Spanish and had difficulty teaching Elementary Spanish, 4) The College didn’t want to lock in too many tenured faculty into the languages department because of possible declining enrollment.

In 1972, Dr. Metzger brought a civil suit against Muhlenberg for $324,916 for wages lost through denial of tenure, claiming that the six-month termination notification was in violation of the faculty handbook. In early 1973, she also appealed to the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission, claiming that Muhlenberg had discriminated against her because of her gender and her Cuban heritage in violation of Title VII.

In September 1974, the EEOC found “reasonable cause” that Muhlenberg had, in fact, violated Dr. Metzger’s rights on the basis of her sex, although not her ethnicity. The report went on to excoriate the College for its hiring and pay practices regarding women, as well as explicitly warning that, while not the matter under review, the miniscule percentage of Black faculty and staff at Muhlenberg could be grounds for further discrimination suits in the future.

In September 1975, Muhlenberg and Dr. Metzger settled in civil court for $75,000; her reinstatement was not included in the settlement.

Kunda vs. Muhlenberg College

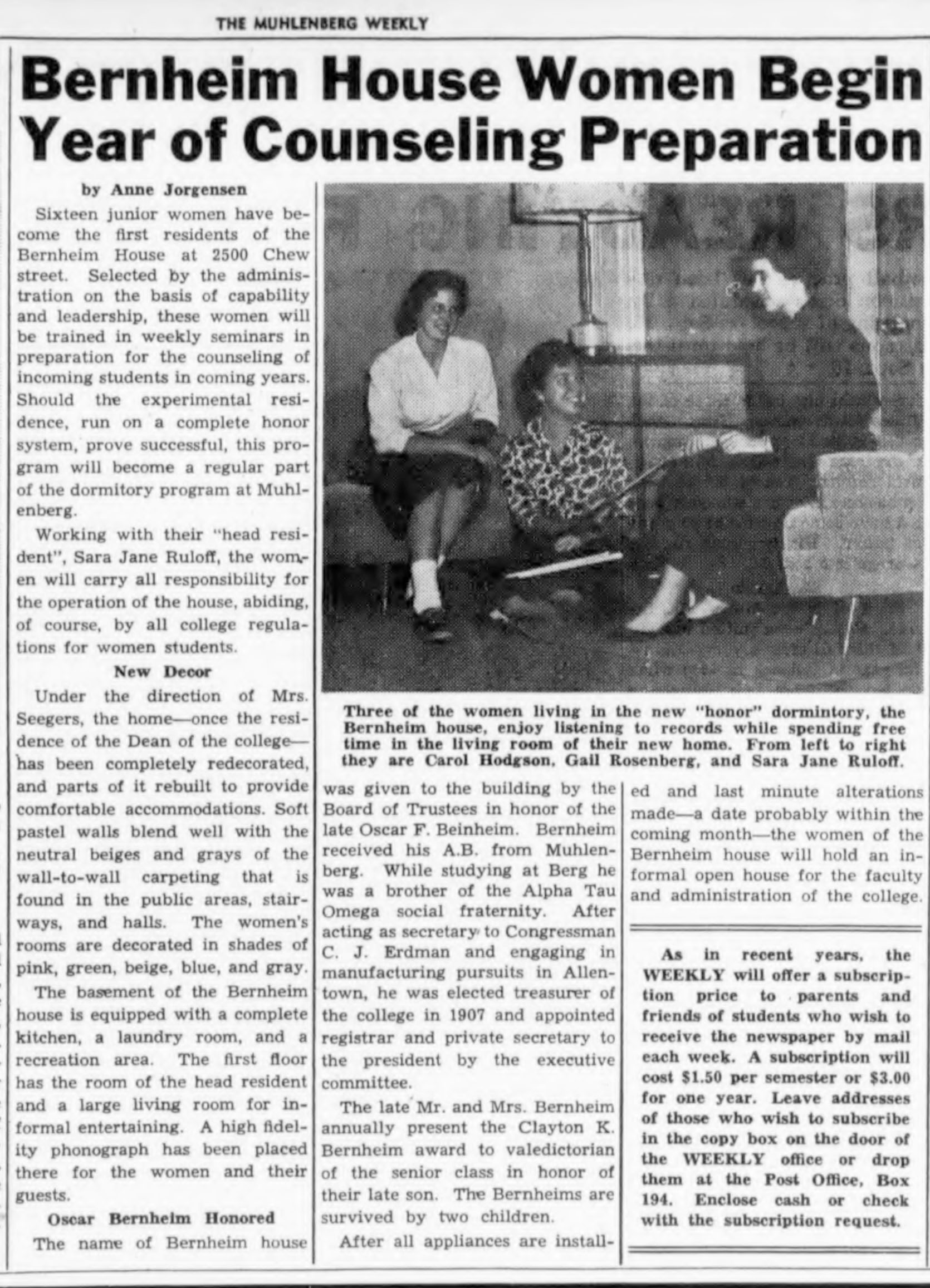

Connie Kunda also joined Muhlenberg in 1966, as an instructor in the physical education department. At the time, she held a bachelor’s degree; she was not advised that holding a terminal degree in her field, a master’s degree, would be necessary for her to ever be granted tenure. Nevertheless, in 1971, her department recommended her for promotion. For the next two years, her promotion, and eventually tenure, was repeatedly recommended and subsequently rejected by the administration under President John Morey; all the while, Kunda was never told the reason for the denial. Eventually, she was issued a terminal contract—essentially fired.

Kunda obtained representation, and her attorneys brought suit against the College, alleging that it was in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. They argued that Muhlenberg’s claim that Kunda’s lack of a terminal degree was the reason for her lack of promotion was a pretext for discrimination based on her gender. Numerous Muhlenberg faculty members testified on her behalf, attesting to her excellence as an instructor and as a member of the Muhlenberg community.

The court found in Kunda’s favor, awarding her reinstatement to her position, back pay, retroactive promotion to assistant professor, and the opportunity to complete a master’s degree within two years, at which point she would be granted tenure. Muhlenberg appealed, and the appellate court upheld the ruling, basing its finding on the facts:

- Three male members of the physical education department had been promoted during Kunda’s time at the College, without regard for their lack of master’s degrees.

- Kunda had never been counseled that a master’s degree was a requirement for tenure, while men in similar positions were so advised.1

Connie Kunda completed her master’s degree. She founded the Wellness Institute at Muhlenberg in 1982, and developed a comprehensive student wellness program. In 1987, she was promoted to full professor, and eventually served as Associate Athletic Director.

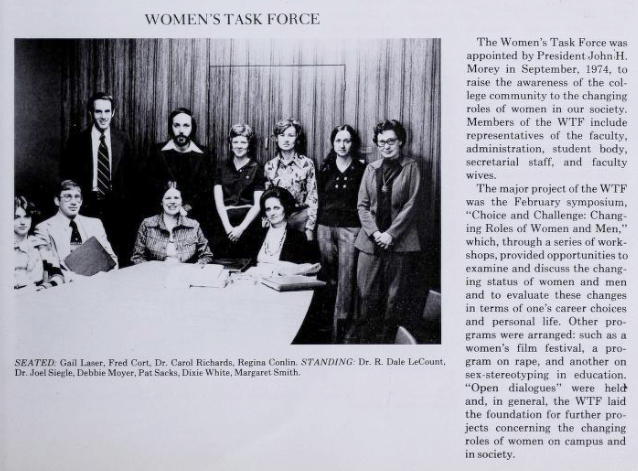

Title IX & the Women’s Task Force

In addition to Title VII, the law that protected Connie Kunda and other women, a new federal law, Title IX, catalyzed more reviews of and changes to practices and policies at Muhlenberg. Enacted in 1972, Title IX prohibits discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that received federal financial assistance. In response, Muhlenberg’s President Morey created the Women’s Task Force (WTF) in 1974 to undertake the enormous task of raising awareness of and education about the changing roles of women in society, identifying potential sexual discrimination, serving as an advisory body to the Muhlenberg community, exploring Title IX compliance across the campus, and much more. Morey appointed Dr. Carol Richards, Foreign Language, as chair. In her position, Richards built a talented team of support from faculty, staff, and students. Her early and extensive outreach to feminist scholars, librarians, and government departments for conference proceedings and scholarly papers, annual reports, books, and Title IX, 1972 Education Amendments Regulations amassed an ambitious collection of materials to guide the WTF’s planning, development, and execution of its charter.

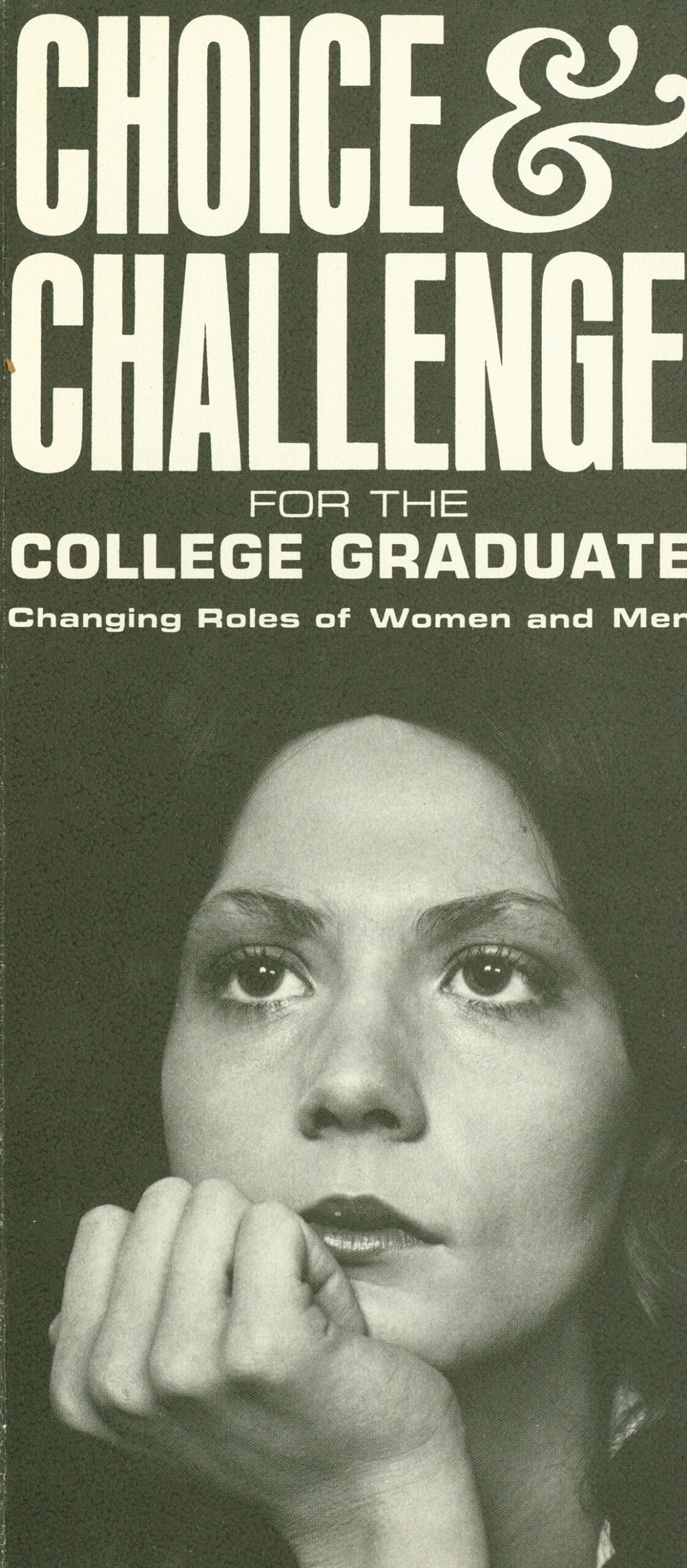

Their first of many meetings, fully supported by Morey, was convened on September 25,1974. Subsequent meetings held through January 1975 focused on the proposed symposium, Choices and Challenge for the College Graduate: Changing Roles of Women and Men. The program explored alternatives open to the Muhlenberg College graduate in careers, in marriage and in the community and was deemed a success.

By September 1975, the WTF announced they had organized themselves into sub-committees, set up procedural guidelines, and met a total of 14 times during the academic year. For example, the Title IX Sub-Committee was established to review Title IX guidelines and explore the College’s policies and practices. Summarizing the report, they projected plans for the following academic year, noting in the Remarks section, “The WTF will continue its educational and support activities; only the College can take steps to change any policies and practices which limit services and opportunities available to women.”

The period between 1974 and 1984 was an especially exhilarating and productive time for the WTF, facilitating changes in policies and practices, enhancing awareness of the rights of women on campus, and strengthening the educational opportunities for students, faculty, and staff. In celebration of 25 years of coeducation, the Board of Trustees proclaimed the academic year 1982-1983 as “Year of Muhlenberg Women” and the WTF created a centerpiece for the year-long celebration featuring a series of lectures including well-known women like Shirley Chisholm, Margot Scharpenberg, and JuhzhiXue, as well the “Women in the Eighties” symposium with keynote speaker The Honorable Patricia Schroeder, U.S. Representative, Colorado, and four workshops. The Women in Politics Workshop was led by Judge Madaline Palladino while the Women and Poverty Workshop was led by Assistant Professor Patricia Dervish of Cedar Crest College. Thomas Hyclak, Ph.D. of Lehigh University led the workshop on Women and Work while Janine Fiesta, B.S.N., J.D., Legal Counsel to Lehigh Valley Hospital led the workshop on Women and Technology.

Frederick Augustus House petition

In the fall of 1975, after efforts that reached to the state level, women were for the first time able to move into an off-campus house (currently the Delta Zeta house). The previous year, a cohort of women had applied to live in the house as part of a “small house” program offered by the Dean of Students office. The women were told that for safety reasons, they must live in a house closer to the heart of the campus, and the house was assigned to male students. The women claimed that this was discrimination on the basis of sex and appealed to the Pennsylvania Human Rights Commission, which affirmed their position. A compromise was reached before public hearings were held.

Women’s Professional Group

Founded in 1985 as a social networking group, the Women’s Professional Group (WPG) worked to “expand inclusiveness of its membership as well as its influence in policy, curriculum, campus programming, student life and other areas”. Under the leadership of co-chairs Jane Flood and Sue Curry Jansen and steering committee members Anna Adams, Christine Sistare, Linda Wallitsch, the Group made a significant effort toward ensuring women’s rights for staff, students and faculty. Faculty especially sought to establish a student bill of rights, to integrate gender issues into the curriculum, and to increase sexual harassment awareness. For example, in 1991, they published The Muhlenberg Women’s Studies Anthology as an outlet for feminist work and as a means for highlighting the strength of feminism on campus (Acknowledgements). Additionally, in February 1992, the issue of A Different Voice was devoted to the issue to sexual harassment and assault, including a list of phone numbers for the Crime Victims Council of Lehigh Valley, a proposed students Bill of Students’ Rights, an article about consent, and a review of Muhlenberg’s policy on sexual harassment. By October of the same year, their policy group created an informal report form to encourage reporting of sexual misconduct.

Their newsletter was eventually renamed to A Different Voice, inspired by psychologist Carol Gilligan’s seminal 1982 text, In a Different Voice. According to Sue Curry Jansen, Department of Communications, the new title views difference as “neither a binary category, nor simply a marker of gender” but as a plurality of “differences that make a difference” (p. 3). The publication featured announcements about conferences and lectures, reviews of books, interviews of visiting scholars, and opinion pieces, among many other offerings. Students and faculty comprised the main contributors. Each edition focused on specific topics such as women’s rights, gender and language, sexual harassment, women’s health, gender and environment, policy making and curricular issues. In fact, in November 1992, the faculty approved the group’s request for a women’s studies minor. In 1993, the group changed its name to the Women’s Issues Network (WIN).

1 Kaplin, William A, and Barbara A Lee. The Law of Higher Education, 2 Volume Set, p. 506-507.